Sheet Metal and Threadbare Light

ABRUZZO TO BRUSSELS - PART II, 2025

Crossing Europe in a Car Half Our Age. Part II: Abruzzo-Home.

Road signs in Italy are made for people who don't need them. Locals are born with an innate sense of direction that no algorithm can replicate. They enter roundabouts with the aplomb of joining a family dinner and leave just as decisively when they've had their share, oblivious to the frustration of those desperately looking for clues to get out. Like me.

I'm doing another full circle while the map on my phone spins in place, trying to keep up but losing the plot. If there had been a sculpture at the center of the roundabout, I'd be able to draw every angle of it from memory by now. But I assume the town ran out of money for art after installing the kilometers of triple-height guardrails that line every single turnoff.

If you want to make money in Italy, start a guardrail business.

Italian road signage is conjecture stamped in sheet metal. Depending on the mood of the land surveyor’s wife the day he put up the sign, you may have to slam on the brakes to cleanly take an exit that was supposed to appear in 500 meters, or be grateful you don't have to walk the distance. The local road crew’s football team must have lost the game the day before they cleaned up the construction site, because they left the 50-kilometer signs behind in frustration.

Every road trip in Italy doubles as a case study in behaviorism.

Cortina d’Ampezzo preparing to host the Winter Olympics

My vanguard claustrophobia evaporated the moment I floored the accelerator onto the A24. The first snow of the season caught the morning sun on the peaks of the Gran Sasso, while clouds—dense as meringue—still lay packed in the valleys. Father and son Verardini were waiting at the Centro Assistenza Porsche Classic in Padova for the engine’s first oil change, ready to rescue us from the mobile sauna the car had become after the air conditioning decided our aging bones needed full-blast heat, all the time. Four days in Venice would be a sensible antidote to eighteen hundred kilometers on McAdam’s tarry invention.

Verardini Centro Assistenza Porsche Classic in Padova

As the A24 gave way to the Adriatic coast and we drove past Ancona, memories of the meat trade emerged. I can't remember when I first met Umberto. I do remember his eyes darting all over the place on either side of a nose that must have looked different before his years in the ring, and ears that bore the brutal impact of too many punches. His ever-present smile disguised a lethal shrewdness for profitable deals; under the shaved stubble on his balding head, his brain seemed to work in permanent overdrive. He eventually became our Italian distribution partner, but only after I’d turned down his proposal to make us the leading television sponsor of the national boxing championships. I suppose I dodged his hook.

Over the years, there were many more I had to dodge and a few I didn't see coming.

Having a former boxing champion as your Italian partner in the early 90s regularly became an engaging conversation topic at dinner parties. Especially once Maurizio—even stockier than Umberto but without the smile—stopped leaving his side, and Umberto's new Mercedes 560SEL seemed to sit quite a bit lower on its springs.

The meat business is concluded at the table of a good restaurant, not in an office. Lunch was at a trattoria in the farmlands near Jesi. There was more tartufo than tagliatelle on the plate. The coniglio in porchetta tasted like proof that evolution has a sense of humor; only Italian chefs know how to monetize it. The second bottle of Rosso Conero served as the deal closer for the day.

We returned to the office happily, Umberto driving the big Merc along the winding country roads, Maurizio riding shotgun, his head working like a metronome: left—center—right, left—center—right. Never pausing, never missing a beat. Not nervous. Not rushed. Just methodical, as if he were sweeping the landscape for movement the way a lighthouse sweeps the sea. I sank into the black leather in the back, hand out the window, fingers lazily hooked over the rain gutter.

Giorgio Mastinu Gallery, textiles at Chiarastella Cattana and coffee at Casa Yali.

Foreign languages have a strange trait: words come easily when they're of no use but remain concealed when you most need them. When Umberto hit the button to close the rear door window on my fingers, the Italian for "window" and "finger" vanished from my brain. The glass rose with a slow certainty to seal the cabin. No safety sensor kicked in. Instead came pain and a boar-like grunting I've never been able to reproduce since.

Whenever you find yourself in an armored vehicle, remember to keep all extremities away from open windows.

If the number of 911 RSs in the Verardinis' Porsche Classic workshop was anything to go by, our car was guaranteed a deluxe oil change and, with some luck, a drive up north in less tropical conditions, with repaired air conditioning. Despite—or maybe because of—a national strike, the train to Venice was perfectly on time.

Venice is usually at its best early in the Biennale: in May, the light is as sharp as the artists and the palazzos as boisterous. Success befits this impossible city as much as it befits the artists who chase an impossible dream. But it was November, and summer had worn the light threadbare. The works at the architecture Biennale looked in need of restoration, the attendants in need of a more lively job.

There is as much room for melancholy in Venice as there is for exuberance.

Thomas Schütte at Punta della Dogana. Venice Transformed People Through Art—Architecture at Palazzo Pisani

But persistence pays. Giorgio Mastinu's gallery is tiny, splendid, and the kind of place you only find once you stop expecting Venice to perform for you. Its opening hours are as eccentric as his curation. He was showing Inchiostri by Ronan Bouroullec, created with the Murano maestro Simone Cenedese—constructivist vases where weight confronts airiness and color tests transparency. His gallery is in the San Marco that tourists miss: the hidden maze of Casa Yali's glass, the textiles of Chiarastella Cattana, and the frames of Ottica Manuela. In these alleys, Venice sheds its skin as a museum and becomes a village again. With greetings, not just looks.

There’s a slowness to this city: the pace of water and salt, calibrated for reflection.

Zoe Ouvrier, Gregor Hildebrandt, and Julian Opie at Palazzo Pisani

The Strange Life of Things by Tatiana Trouvé at Palazzo Grassi

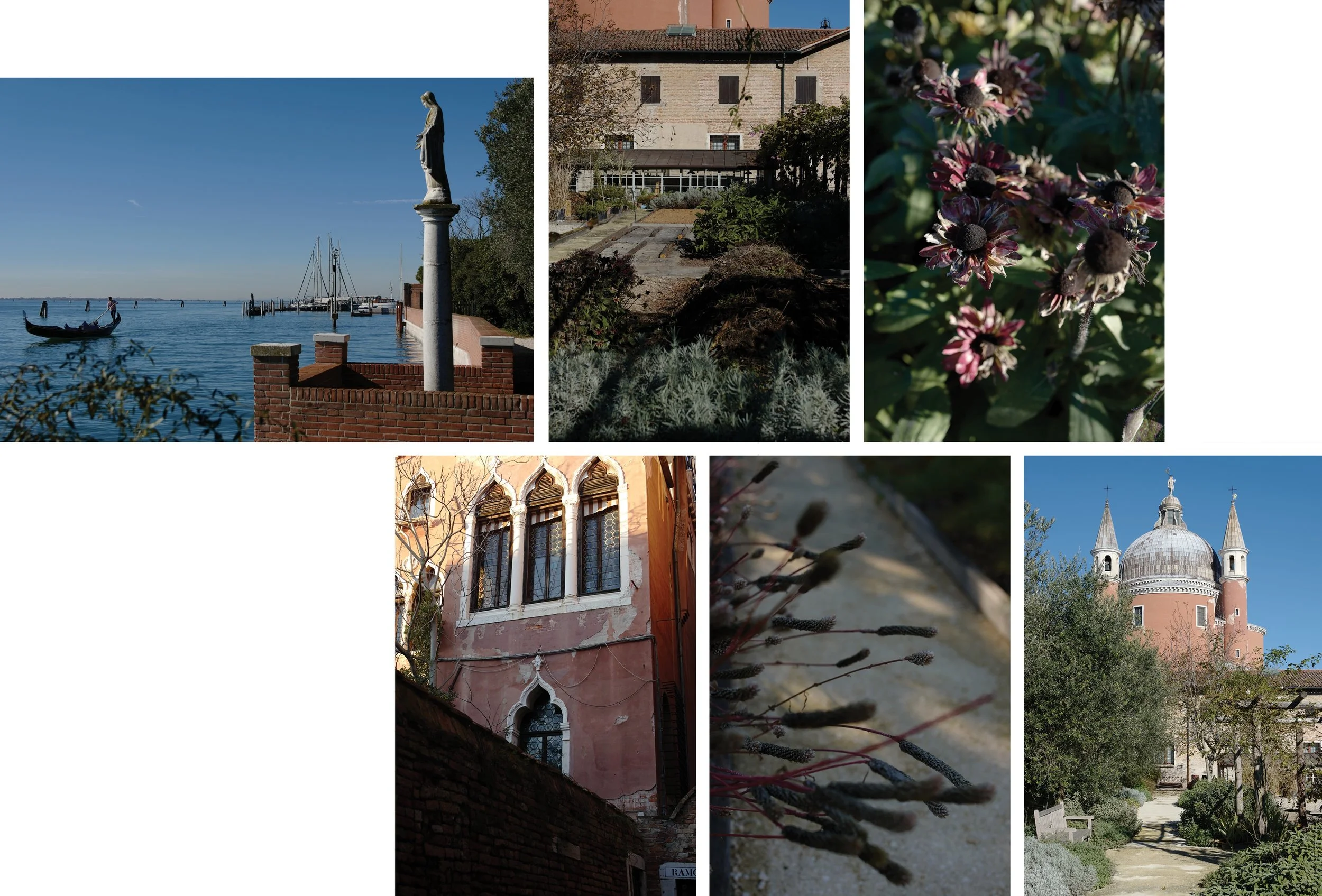

At the Redentore Convent Gardens on the Giudecca, the hours thin out and life is reduced to essentials: an olive grove, a well, and a hortus simplicium of vegetables, herbs, and flowers. The convent’s brick walls hold an intimate simplicity. Beyond them, the lagoon opens wide enough to make you feel the pull that built Venice in the first place: appetite, reach, and the temptation of elsewhere.

Leaving Venice isn’t painful; it’s sobering. The water slaps the hull of the vaporetto as it grinds against the floating pontoon at Ferrovia. Visitors crowd the bow, transfixed, phones clicking and glowing. The marinaio barks at a family wrestling four enormous suitcases on board before the last passengers have stepped off. Like many Venetians, we are turning our backs on the water. We leave for the mountains, seeking terra firma.

Venice Architecture Biennale, Scandinavian, Australian and Swiss Pavillons

Australian Pavillion at the Venice Architecture Biennale and Fortuny Showroom and Factory

I could have driven to Cortina with my eyes closed if it weren’t for one more roundabout lacking any form of signage. According to Google, it didn’t even exist. With just over a hundred days left to the Olympics, the province of Belluno is frantically trying to engineer a fluid passage to town over single-lane mountain roads that have been clogged since we first came to the valley more than twenty years ago.

Italy has a solution for every problem. It’s called confusion. Confusion sends you to Cortina along the Cadore instead of the Boite valley. That's an hour's detour but a traffic problem solved for everyone not part of it.

Cortina is expecting. Largo delle Poste is slated for restoration; the Gellner buildings will shine again, and an underground car park will be reserved for residents. Piazza Stazione remains a vast construction site; two more years, they say, before its own underground parking is finished. Franz Kraler and Louis Vuitton are refurbishing. Prada is building a new store. Bar Sport patrons will spill onto Corso Italia for Campari spritzes. Some shoppers will walk into the Coop in fur coats; others will wander in wearing ski boots.

Fortuny Showroom and Factory

Where the Bob Bar used to be is now the scarred landscape of the Cortina Sliding Center—€118 million carved into the hillside. Its sixteen concrete curves may never be profitable. Profitability isn’t on the Olympic agenda; image is. What does a winter-sports image boost mean in a place that’s snow-reliable only thanks to cannons?

There is more frantic roadwork as we drive north on our way home. The roads widen the moment we cross into Südtirol; they are smooth and perfectly maintained. The engine purrs. The Brenner beckons. There’s an off-camber ninety-degree downhill bend near Innsbruck: tricky when wet, outright dangerous in snow.

Redentore Convent Gardens

By the time we reach the German autobahn, we’ll have driven 2,500 kilometers. The rebuilt engine will be run in.

Time to floor the accelerator and give the modern cars a decent run for their money despite their digital leash.

I'll grin from ear to ear.

Toujours taré, ce mec.

Subscribe to get full access to the newsletter and publication archives.