Vajont: Engineering, Impunity, and Aesthetics

LONGARONE, 2026

From the 1963 Vajont Disaster to Michelucci’s Santa Maria Immacolata: Architecture as Indictment.

It was mass murder.

This is what the few survivors shout—those rendered unsteady by the terror of that avalanche of water and by the despair of finding themselves alone, powerless before a reality that had become nothing. Or rather: stones and slime, fused by the blood of their loved ones. A reality that, in seconds, altered the face of entire villages—and yet had been foreseeable for years. Even at the start of work on the great Vajont hydroelectric reservoir, engineers knew they were building on unstable ground, terrain that could slide.

Mass murder, therefore, must be shouted aloud, so the cry can shake the public conscience. So that people, whose lives never count for anything to those in power, will finally sweep away, with anger and indignation, those who squander thousands of human lives with impunity, coldly, for profit and control. (1)

On October 9, 1963, at 10:39 PM, a landslide—about 260 million cubic meters of rock, nearly 2 kilometers wide—raced down Monte Toc at roughly 110 kilometers per hour. Within 45 seconds, the debris displaced the Vajont reservoir and drove a 250-meter-high wave over the dam built three years earlier. What came first felt like a shockwave: a force that struck before the water.

So strong that many victims were found naked, their clothes torn away.

Longarone instantly became a bleached wasteland. More than 2,000 people died. The dam survived. Only 30 children from Longarone did too. To this day, it is remembered as one of Italy’s most devastating disasters.

Or, as journalist Tina Merlin exposed soon after, not a natural disaster at all: a man-made one. Against the advice of geologists, the dam—then among the tallest in the world, a technological trophy—was built to power the rapidly growing Italian economy. “Toc” means “rotten” in Friulian, one of the region’s native languages. Locals called Monte Toc “the Walking Mountain.”

But business interests overruled both local knowledge and expert warning. Disaster engineered into the inevitable.

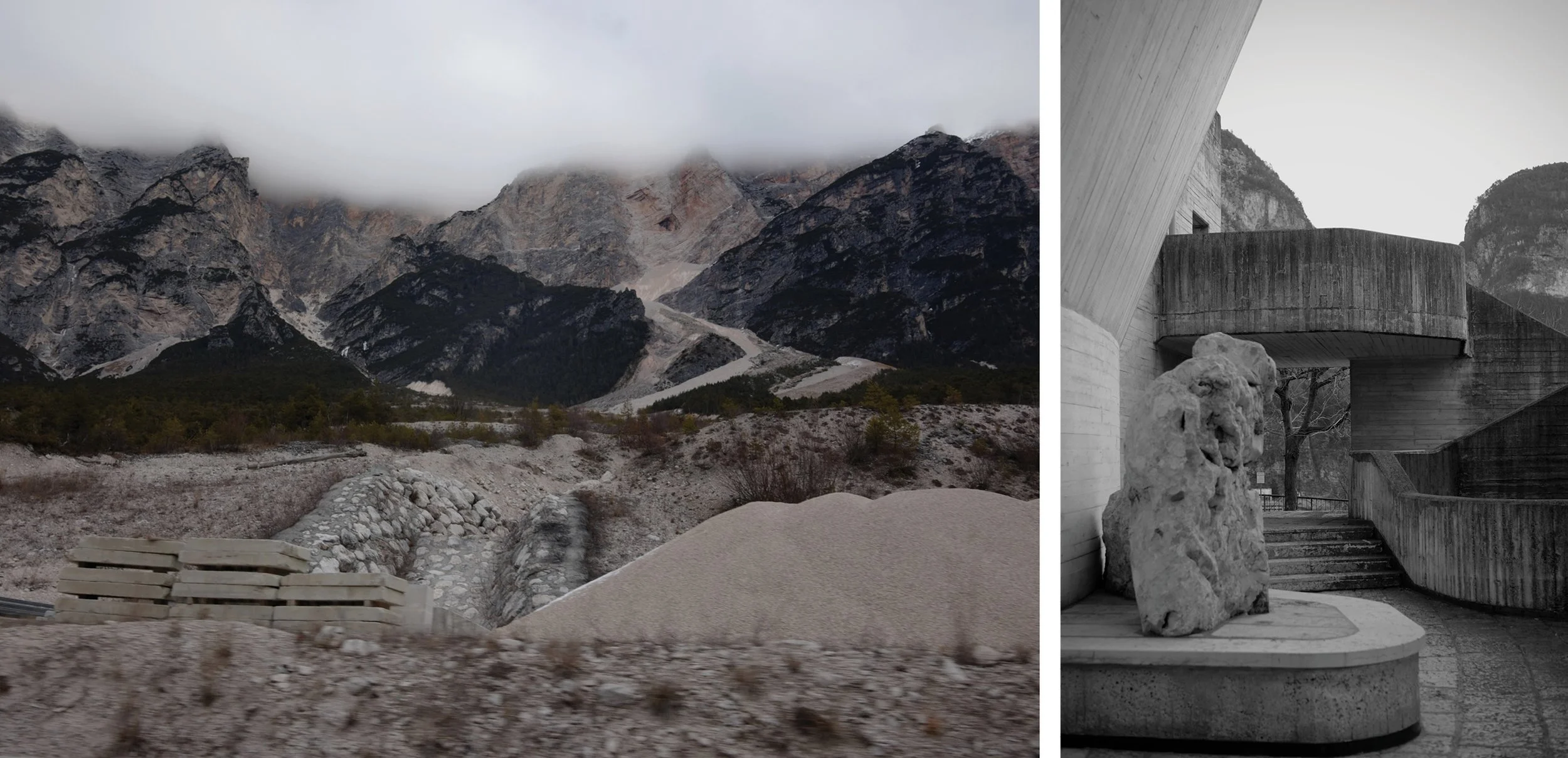

The entrance to the Dolomites is brutal. The muted Veneto landscape crashes into steep limestone. Vineyards give way to larch forests. And as the valley narrows, the Piave eradicates all memory of a gentler life on the plains.

That’s when you meet the church that tries to hold what can’t be held.

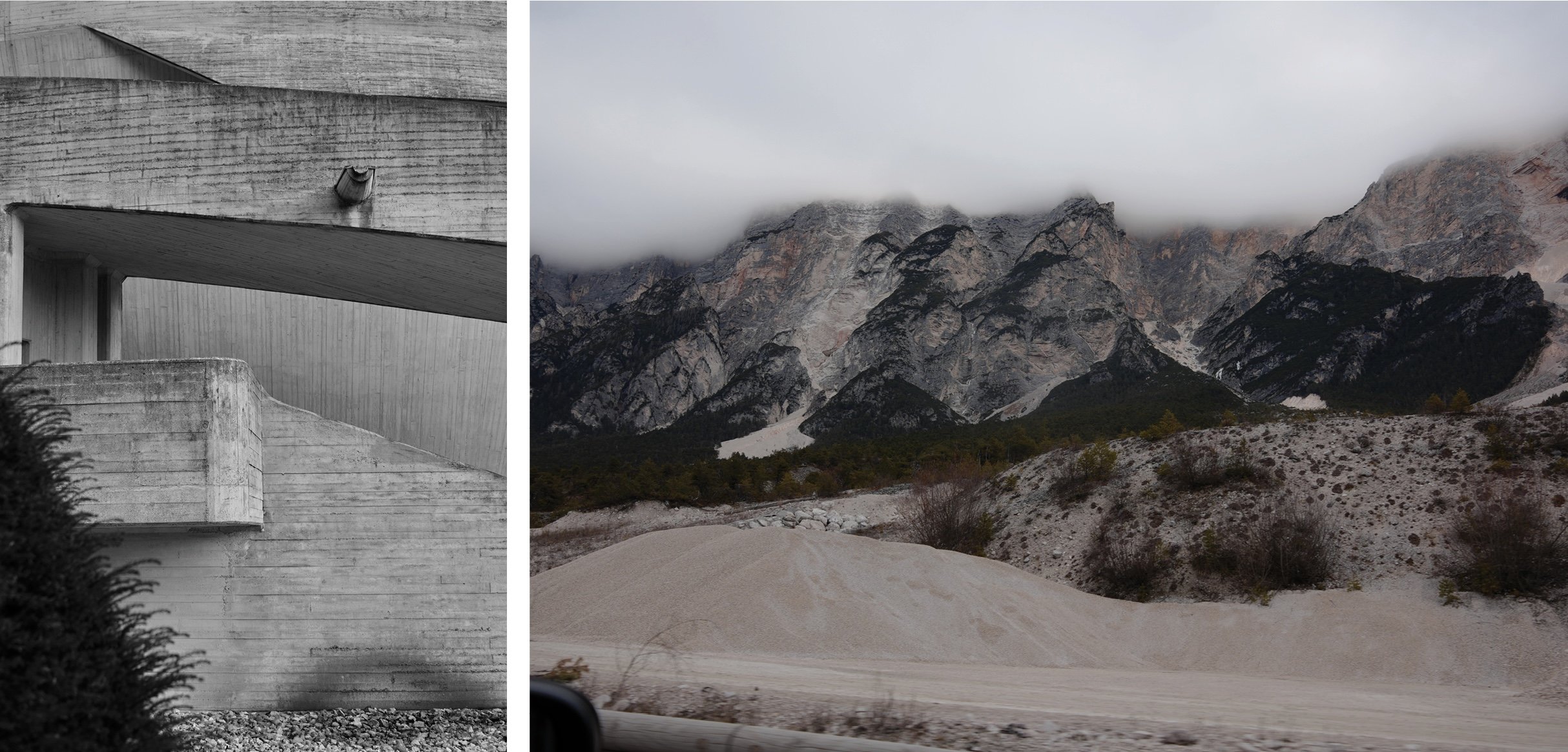

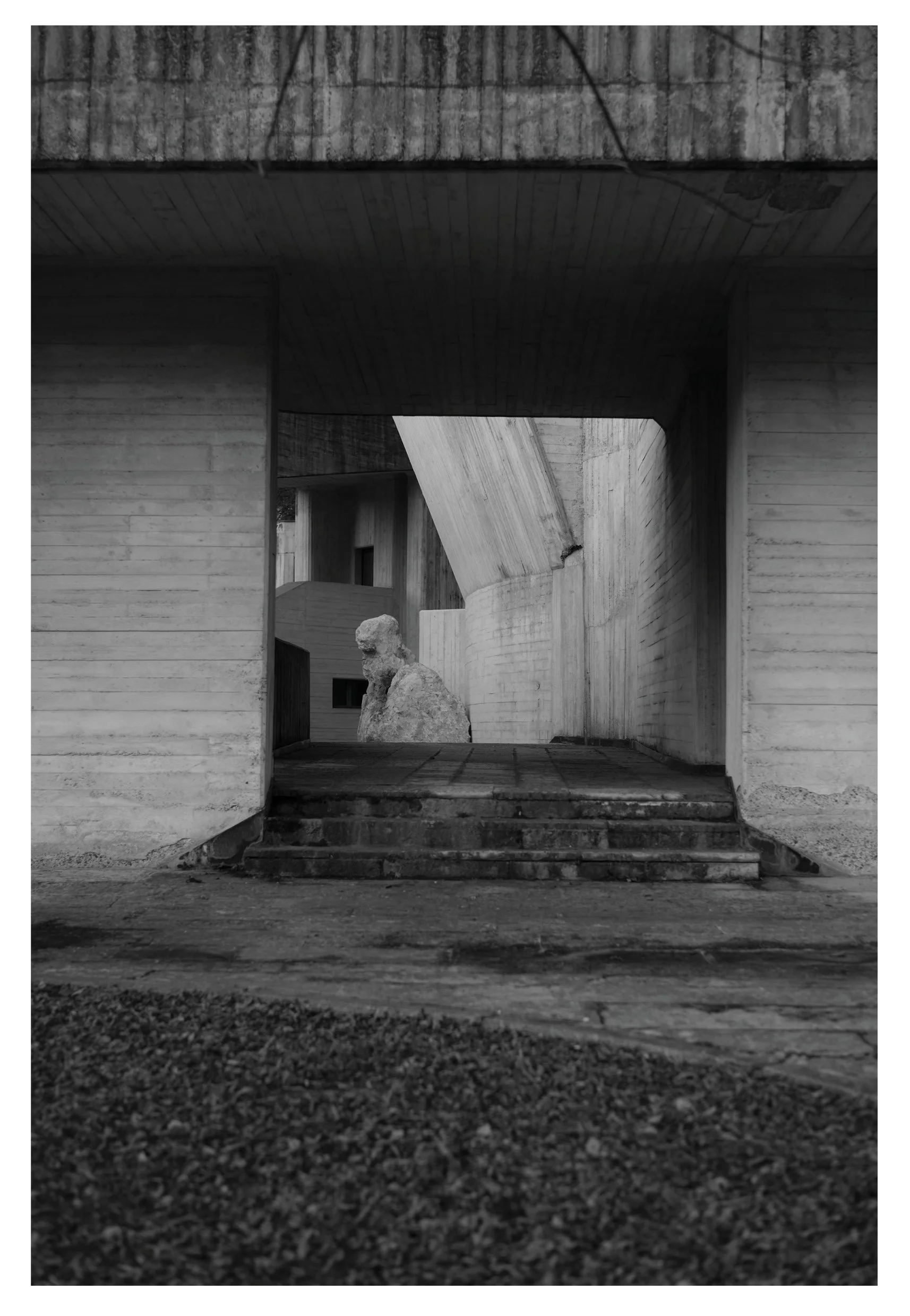

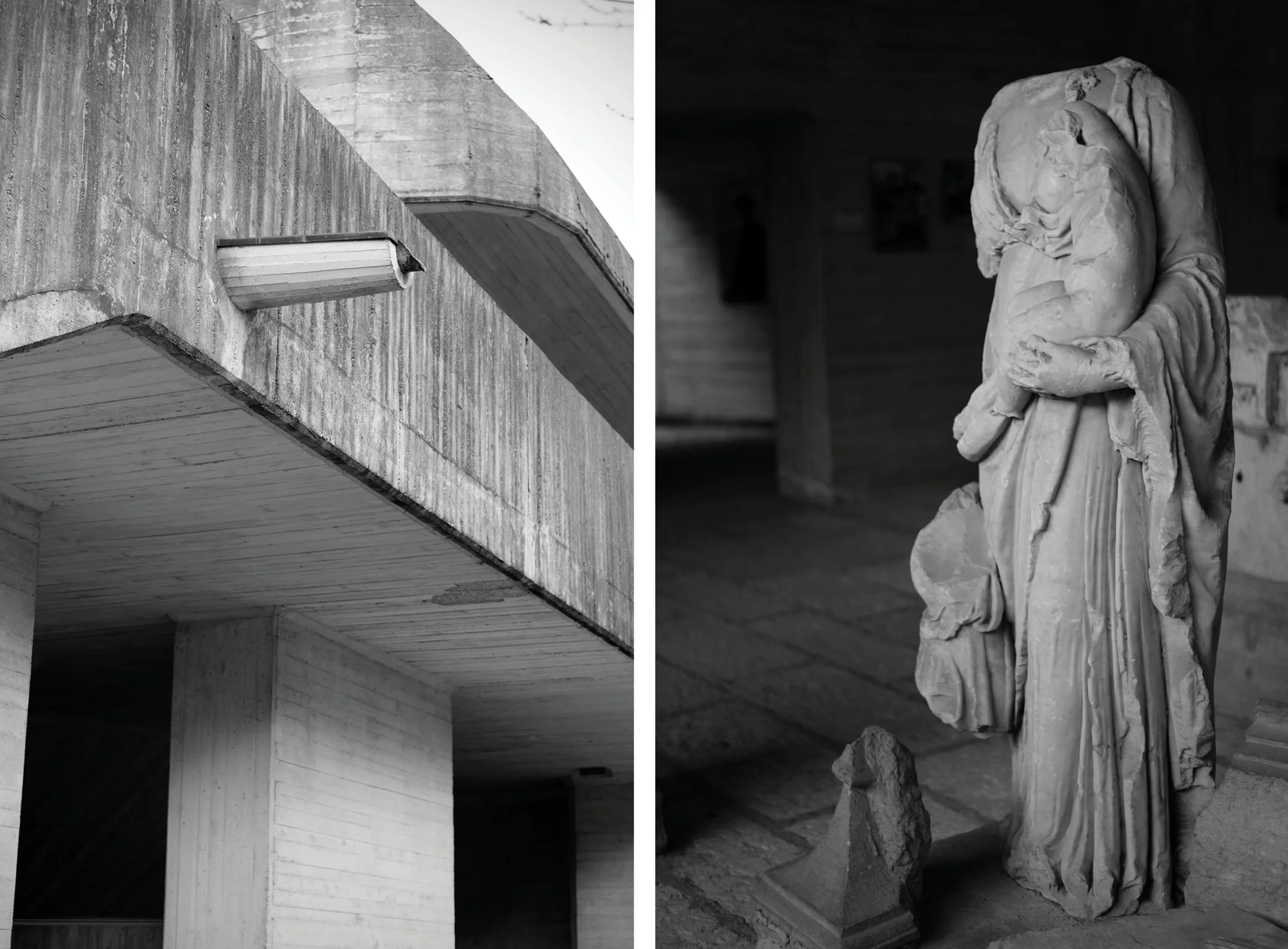

You enter Santa Maria Immacolata, and the chill hits you low. An amphitheater of darkness where light is sparse and the monolithic white marble altar cuts against the grey, raw concrete. A salvaged Christ—armless, legless—is pinned out of reach, fixed to the architecture itself. As if the Lord himself is helpless against what men will do for profit.

From the external amphitheater above, you see the Vajont dam. It is still standing across the river, abandoned by its purpose. Here, Giovanni Michelucci’s architectural concept snaps into focus. Concrete answering concrete. Not just a material for building, but a material for memory. The church’s sweeping walls rhyme with the dam’s arc: two curves made to contain. One to serve a system. One to hold a wound.

One failed. The other remembers.

Somehow the building echoes the Dolomite landscape. The concrete has weathered to the exact hues of the mountains on a January day heavy with clouds: threatening but awe-inspiring. Grounded and celestial at once. Sinuous in some places. Ragged in others.

The sound is muted as you walk the church's winding ramps. A brass plaque with an endless list of victims covers an entire wall. It descends into the crypt strewn with broken sculptures, bells, and fragments of the old church that stood at the exact location. Survivors spoke of a deafening noise that still haunts them, like metal shop shutters crashing shut.

Then all went black for them.

The Italian language has two words for the English survivor: superstite and sopravvissuto. For the superstiti—from super + stare, "to stand"—that night determined their lives. They are like the dam and the scarred Monte Toc, eternally reminding us of a tragedy that should never have happened. The sopravvissuti—from super + vivere, "to live"—chose to live their lives despite the disaster and share their experiences. They are like the Santa Maria Immacolata church.

They remind us: impunity has a cost.

But not for all.

(1) Tina Merlin, “E' Stato un Assassinio,” L'Unità, October 11, 1963 (translated by the author)

Subscribe to get full access to the newsletter and publication archives.